Ninety nine years on from the start of World War One there is a group of men who’s service has long since been forgotten about, these men were Eastern European immigrants from Russia and the Baltic States who had settled in Scotland.

So how did these men come to settle in Scotland?

Many of them were escaping the clutches of Czarist Russia’s Army, where they would serve many years for little reward. In the 1890s many decided that enough was enough and left Russia, Lithuiania, Latvia and Ukraine with the intention of moving to the United States.

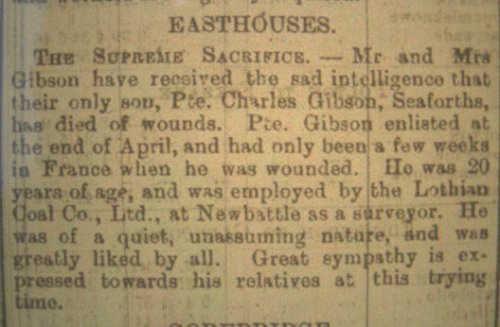

At this time there was an active trade between German and Baltics ports and British ports such such Leith ,on the east coast of Scotland, with coal being a prime export from Scotland. One of the main exporters was the Lothian Coal Company with numerous ships to and froing.

Rather than come back empty, the filthy coal ships offered immigrants cheap passage to a new life, which the immigrants thought would be in the USA. To their horror they were deposited in Leith (port town of Edinburgh) without a job and homeless.

The Lothian Coal Company was not slow to take advantage of their situation, the Lady Victoria Colliery had just opened in Newtongrange, many men were needed to man it’s new and highly productive coal seams. At first Scotish families moved through, mostly from Lanarkshire, however their numbers were insufficient and the Eastern Europeans were offered a job and and a house, many, especially those with a wife and family,had little choice other than to accept.

They settled in two main areas, the bulk in Bellshill, Lanarkshire and the rest in Newtongrange, Midlothian. Most came from Suwalki which lies in the NE of current day Poland and SW Lithuania.

And so my village of Newtongrange became home to several hundred ‘Russian Poles’ as they were christened. Coming from all walks of life, few if any had ever been down a coal mine, most spoke no English, and a number were illiterate. Most settled in their new home and by 1906 there were around 200 Lithuanians as well as a number from Latvia and Ukraine living in the village, by the outbreak of war that number had increased to around 600 ,and about 1 in 5 of the population of Newtongrange were immigrants.

Technically they were Russian citizens at this time, and as such ‘friendly Aliens’ who had to register with the Police at the outbreak of the Great War, and had certain restrictions on their movements. Unlike the Germans and Austrians in the community there were still free to live and work in the village.

Many men from the village enlisted in the Army, including a group of around 25 Lithuanian miners, who wished to join the famous McCrae’s Battalion, the 16th Royal Scots. They were initially accepted by were sent home shortly after as they could not read or write in English.

Not all were rejected however, men such as the Mikolajunas brothers Jan and Stanislaw were accepted into the Royal Scots and the Lancashire Fusiliers, Ukrainian Vasily Nikitenko boarded the bus into Edinburgh where he enlisted in the Royal Garrison Artillery. This pattern continued through 1916 with the occasional man enlisting, but most remaining in the coal mining industry.

This was about to change however, conscription had been introduced in early 1916 for British citizens, ‘Russian’ citizens were not subject to conscription, at least that was until 1917 when a treaty was signed between Russian and Great Britain allowing both to conscript each other’s citizen into their Army.

An ultimatum was issued to the Eastern Europeans, they were to make a choice, enlist in the British Army or return to Russia to fight for the Czar. Around 2/3rds of them decided to return, believing they were fighting to preserve their national identity. Not a single man who chose to fight for Russia was ever seen again, shamefully their families were evicted, rounded up and deported, again many never to be seen again.

As the for the others, well most were sent in job lots to Infantry regiments, from my research I have identified groups sent to the Royal Scots, Kings Own Scottish Borderers, Scottish Rifles and the East Yorkshire Regiment, My theory is that they tried to keep the men in groups to overcome the language barrier, with an English speaking man in each group.

In 1917 the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia sent shock waves through the Allies and many of the ‘Russian Poles’ were viewed with much suspicion as potential ‘Reds’ and were removed from Infantry battalions and sent to unarmed Labour battalions. However many of the men who had proved themselves reliable under fire remained with combat units until the end of the war.

Inevitably some became casualties and a number made the ultimate sacrifice, mostly in 1918.

If you take a walk through Newtongrange Park you will come across the war memorial on which are these names

Pte Klemis Poliskis, Scottish Rifles, Pte Juozas Sanalitis, Kings Own Scottish Borderers, Gnr Stanaslaw Scortolskis, Royal Field Artillery, Pte Justinas Tutlis, Royal Scots all of whom were Lithuanian.

In 2007 I successfully campaigned to have another name added to the war memorial, it was that of Gunner Vasily Nikitenko, who if you recall, volunteered in 1916.

In 1918 Vasily was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry during the German Spring Offensive, sadly he did live long after the award, on the 28th May, 1918 he was manning his gun when a stray shell landed killing him and wounding a number of others.

I was also able to assist Geraldine Bruin, the Great Neice of Zigmas Vilkaitis to have his name added to Glenboig war memorial in Lanarkshire, you can read his story here

After the war most of the Lithuanians moved away from the area, mostly to the United States, the majority of those that remained took British nationality and adopted British names, men such as Jan Mikolajunas, who became John Nicol. There is now little trace of the Lithuanian community in Newtongrange or elsewhere in the district, I estimate that 50 to 100 Eastern European men from Newtongrange served in the Army and would welcome contact from anyone related to them.

John Duncan – Honorary Board Member of the Scottish Lithuanian Community